A Fountain Flowing With Music

Featured“This isn’t happening in Nashville. This isn’t happening in New York or LA or Memphis, Muscle Shoals or anywhere you associate with recording. It’s not happening anywhere but right here in Fountain.” – Jimbo Mathus

This article originally appeared in The Daily Reflector on August 18, 2025.

By Kim Grizzard

Audiences from Tribeca Film Festival in New York to Telluride, Colorado’s Mountainfilm got a glimpse into the life and work of artist Freeman Vines at spring premieres of a short documentary about the guitar maker and musician. But over the last few years, folks in Fountain had a front-row seat.

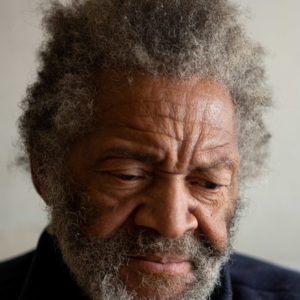

Freeman, who died in March at age 82, spent the final days of his life carving out the musical legacy he wanted to leave behind. Despite a diagnosis of diabetes and multiple myeloma, he often worked through the night at his studio on Wilson Street, searching for a sound. His eyesight was limited, but never his vision.

He imagined that old storefronts could be turned into spaces where traditional voices of American music could be heard so that they — and this place — could be preserved. And from his wheelchair, he watched and listened as Music Maker Studios was born.

“That was Freeman’s idea,” Music Maker Foundation co-founder Tim Duffy said of the century-old buildings that have been remade into a photography studio and recording studio that began operations last year. “We built the studio kind of in honor of Freeman Vines. He loved this town.”

Fountain, established in 1903, grew up along the railroad in western Pitt County halfway between Greenville and Wilson. It is home to nearly 400 people and about 150 of Freeman’s guitars.

Singer-songwriter and guitarist Jimbo Mathus routinely selects an instrument from Freeman’s collection on the wall in the studio to play when he comes to Fountain to record albums. Mathus, founder of the band Squirrel Nut Zippers, makes what he calls “a 15-hour commute” from Oxford, Mississippi, to Fountain to work as a consultant and producer for Music Maker Studios.

Isn’t Oxford bigger than Fountain?

“Pretty much any town is bigger than Fountain,” Mathus said, laughing.

Isn’t Nashville closer?

“This isn’t happening in Nashville,” Mathus said. “This isn’t happening in New York or LA or Memphis, Muscle Shoals (Alabama) or anywhere you associate with recording. It’s not happening anywhere but right here in Fountain.”

In the year since Music Maker Foundation turned part of Fountain’s dilapidated downtown into a recording studio, more than half a dozen albums have been made here by artists whose music, like those buildings, was in danger of disappearing from the landscape. With funding from the Robert and Mercedes Eichholz Foundation, artists like 80-year-old Fred Thomas, who played bass with James Brown for more than three decades, are able to record their music for free.

“A lot of independent labels are drying up,” said Denise Duffy, who co-founded Music Maker with her husband in 1994. “For less famous artists, it’s getting harder and harder for them to get record deals. So this is a way that these artists can get a high-quality recording to try and support their careers. Also these traditional artists can be documented for posterity, for our culture.”

Music makers

Based in Hillsborough, Music Maker Foundation has helped hundreds of artists in its decades-long quest to preserve the musical traditions of the South, including blues, gospel and folk music. The nonprofit organization has worked with talent ranging from folk artist Carl Rutherford to blues musician Earnest “Guitar” Roy and gospel groups like the Vines Sisters.

“Gospel music was essentially minted here,” said Tim, a Connecticut native who moved to North Carolina in 1981 and now considers himself a “chosen” Southerner. “This musical tradition we tapped into is probably one of the oldest oral past musical traditions in the United States.”

While working to explore that musical history, Tim, a folklorist and photographer, discovered that any effort to preserve traditional arts would require sustaining traditional artists. The Duffys developed a sustenance program, focusing their efforts on the most vulnerable musicians — low-income senior adults who, despite their talents, had spent their lives as part of the working class.

“It wasn’t because we really wanted to be a social work organization,” Denise explained. “It was just our artists couldn’t make it to a gig because there was no way they could make the car repair. They didn’t have their guitar because it was in the pawn shop to pay the light bill. They had splitting headaches because they couldn’t afford their blood pressure medication.”

That was the situation a decade ago when Tim learned about Freeman, “an eccentric guy who makes these janky guitars.” When he showed up with a camera at Freeman’s home in rural Greene County, there were guitars, in various stages of completion, everywhere. Some were hidden in plain sight and a few were in the ground.

They were made from unconventional materials, many of them found objects such as radio parts or an old chest of drawers. Freeman, the son of a sharecropper, liked wood with a history, so he worked with what had been salvaged from a Steinway piano, a mule trough and even a tree used in a lynching nearly a century ago.

“He was an artist,” Tim recalled. “Whatever he touched was art.”

But due to Freeman’s diabetes, he had all but ceased work on his hand-carved guitars.

“His hands were swollen, and he could barely see,” Tim said in an interview in 2020, the year that Freeman’s “Hanging Tree Guitars” art exhibition made its premiere at the Greenville Museum of Art. Freeman’s exhibit went on to tour the country, and a book by the same name garnered attention from NPR, Rolling Stone and Smithsonian Magazine.

“But I think what really helped him, besides the material things that Music Maker does,” Tim said, “is we give artists like Freeman and many artists that are elderly a purpose.”

For Freeman, that purpose was the search for a sound, one he recalled hearing in his younger days but that had eluded him for more than half a century. Music Maker Foundation set Freeman up in his own studio space in Fountain where he went to work, seemingly re-energized by the reception his instruments had received. He even began reworking pieces that had been part of the art exhibit, crafting them into usable instruments rather than sculptures.

“I had all sorts of people come here and offer a lot of money; he wasn’t interested,” Tim said, adding that one art expert had recommended that the necks be removed from the guitars and the bodies should be marketed as art. Freeman declined.

“Almost everything (from the exhibit) went back to his shop and he worked on them,” Tim said. “He said they weren’t done.”

A dream come

Neither was Music Maker Foundation. Once the Duffys got Freeman settled into his studio, they began eyeing neighboring property for a larger project. Although the foundation had produced more than 200 albums, it had never had a dedicated studio space to call its own.

The Duffys decided to set up shop next to Freeman in Fountain. They purchased the town’s former library at public auction and bought the adjoining building from the local senior center. Both were run down and needed significant repairs, which Music Maker hired local contractors to complete.

“It was way beyond what the town could afford to repair,” former Mayor Kathy Parker said in an interview. “Tim and Denise have done wonders. Energy is what is needed. They’re just full of energy.”

Although Parker retired in 2024 and moved back to her native Maine, she still follows the progress on Music Maker Studios in Fountain. She hopes the musicians coming in to record, coupled with the presence of an established music venue, R.A. Fountain General Store, will make music a focal point for the town.

R.A. Fountain owner Alex Albright said that while Music Maker Foundation maintains its Hillsborough headquarters, the recording studios give it a strong presence in Fountain.

“It’s a transformative thing for this town,” said Albright, a retired East Carolina University professor and a former Pitt County commissioner. “They have purchased property. They’ve put the muscle into a renovation, and they’re bringing people here and employing people making records.

“When they do a recording session, there are eight, 10, 12, 15 cars in the alley,” Albright said of the space, which has informally been named Freeman Vines Alley. “There’s all this activity. Tim and Denise are doing a great job of helping resurrect this town.”

With Music Maker’s purchase of the second and third buildings in 2022 and 2023, Fountain was on the cusp of a rebirth of sorts. But some wondered if Freeman would live to see it. Diagnosed with cancer, he was given three months to live.

“I thought it was it; everybody thought it was it,” Tim said. “They tried to make him a ward of the state. It was awful. He said, ‘No, I want to come back and build guitars.’ So he came back here.”

Freeman seemed determined to live out his final days in his studio. The space was never intended to be a studio apartment, but that didn’t matter. Folks in Fountain took care of Freeman. Paulette Pittman took it upon herself to feed him, stopping by from work at the post office next door to check on him daily.

“I could see he wasn’t eating like he should, but I cook every day, so I started bringing him supper at night,” said Pittman, who grew up in Fountain and knew Freeman’s sisters, members of the gospel group The Vines Sisters. “Then I saw him in there one morning trying to cook breakfast on a hot plate, and I said, ‘You know what? I’ll just bring you something to eat every morning when I go to work — and some coffee.’

“He loved cheese biscuits. He loved a certain kind of bacon and a certain kind of sausage. I know more about what he loved than I know what my own kids like,” she said. “He’d always thank me, and he’d always brag on me, which he didn’t have to, but I did it because that’s the thing to do. He needed the help.”

Pittman pitched in again when artists coming in to record at Music Maker Studios needed a place to stay, since the nearest hotel is about 20 miles away. Musicians have the option of bunking nearby at her husband’s hunting lodge, rather than driving back and forth to Greenville.

“It’s just a place to be left alone and just focus on your art with people that care about you,” Mathus said of the rural recording studio and its out-of-the-way accommodations. “They’re not trying to hustle you. You really get a community, family vibe going.

“There’s no way that I would go to Nashville this often to record because there’s not the feeling there that I want,” he said. “It’s so cut-throat. I do stuff there, but to me this is a dream come.”

Finding the sound

The opening of the studio also fulfilled a dream for Freeman, who lived two years longer than most anyone expected. Given Freeman’s prognosis, Tim had worried that his friend might never get to sit in on the first recording session, but Freeman lived to witness five of them.

“This whole thing he’s been obsessed with, making the sound out of electric guitars, he was actually able to hear it come to fruition on recordings,” said Mathus, who would keep the door open so that Freeman could come in on his wheelchair to listen. But mostly, Freeman liked to sit outside the storefront, taking in the sound from the sidewalk.

“You could see him out there on the sidewalk listening, smoking a cigar and just in contemplation, listening to the sound coming out of the control room, out into the street, you know, blowing around Fountain,” Mathus said. “He had some of the best days of his life at these recording sessions. I know because he told me.”

Despite his declining health, Freeman increased his productivity in his remaining months, completing as many as 40 guitars and even leaving behind directions for how some others needed to be altered or improved.

“His instructions were quite clear. ‘Anything you need to change, change,’” Tim said. “It’s all searching for the sound. They’re not to go into a museum.”

With Freeman gone, his former workshop has been converted into a reverb chamber for studio recordings. The Duffys refer to the space as a “Freeverb” chamber that honors Freeman’s memory by helping to create the sound he spent the better part of a lifetime pursuing.

Like his memory, Freeman’s guitars fill Music Maker Studios, hanging side by side in storage closets and lining the walls as a kind of mural saluting their maker. But they are not simply displayed. They are played.

During recording sessions at the studios, Mathus has used more than a dozen of the instruments that Freeman built.

“He would get parts out of stuff he salvaged off the streets,” Mathus said. “But when you pick them up, they play like top-of-the-line instruments, and the sound is so unique. So mission accomplished.”

Tim believes almost nothing gave Freeman more joy than to see his instruments fulfill their purpose.

“They were meant to be not trading cards but used to search for the sound, and he stuck with that line until the end,” he said. “He was so proud, so happy to see that. I think it inspired him to make more guitars and see that his idea had a purpose. We’re finding his sound. We took him seriously.”

Get involved

& give back

The Music Maker Foundation is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that depends on thousands of supporters. Together, we work to meet the day-to-day needs of the artists who create traditional American music, ensure their voices are heard, and give all people access to our nation’s hidden musical treasures. Please contribute or shop our store today.