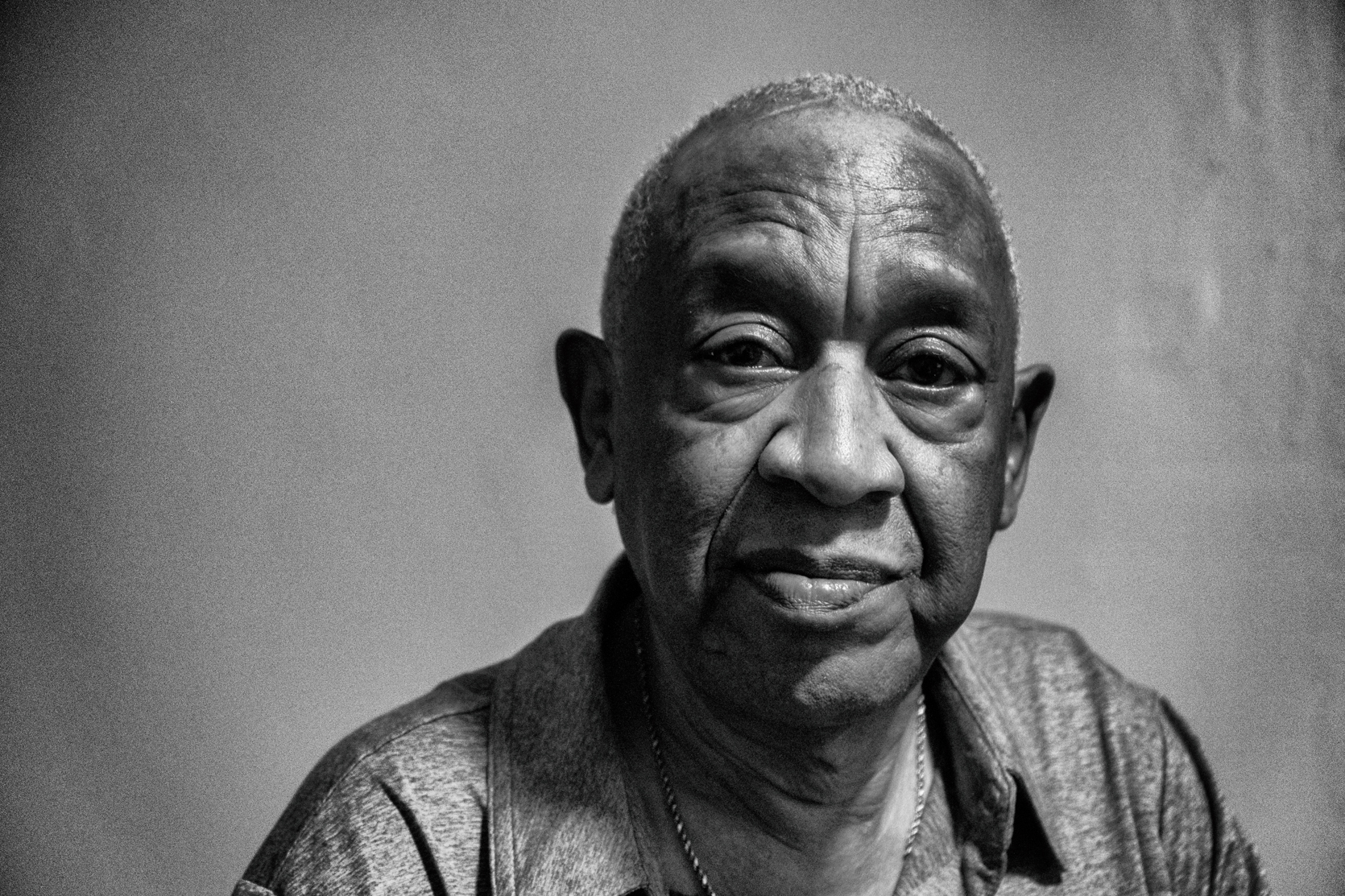

Discover the Music and Life of Hermon Hitson

BluesMeet the Atlanta, GA artist who mixed psychedelia and soul music, played the chitlin circuit, collaborated with Jimi Hendrix, pioneered funk music, and has reemerged of late through joining the Music Maker Foundation.

By Nick Loss-Eaton

When Music Maker Foundation took the latest version of its Music Maker Blues Revue to the Telluride Blues & Brews Festival in Colorado, the band included a guitar player and singer from Atlanta named Hermon Hitson. He was brand new to the Music Maker family, but he had a musical track record of more than 50 years, playing with the likes of Jimi Hendrix, James Brown and many others. When Hermon first met the Gospel Comforters — another band we brought to the fest — they all looked at his shoes.

“Where did you get those James Brown boots?” a member asked. “They don’t make those anymore. Only James had those made.”

There Hitson stood, in Colorado, wearing a pair of custom-made boots that no one but James Brown himself and those who played with him could ever put on their feet.

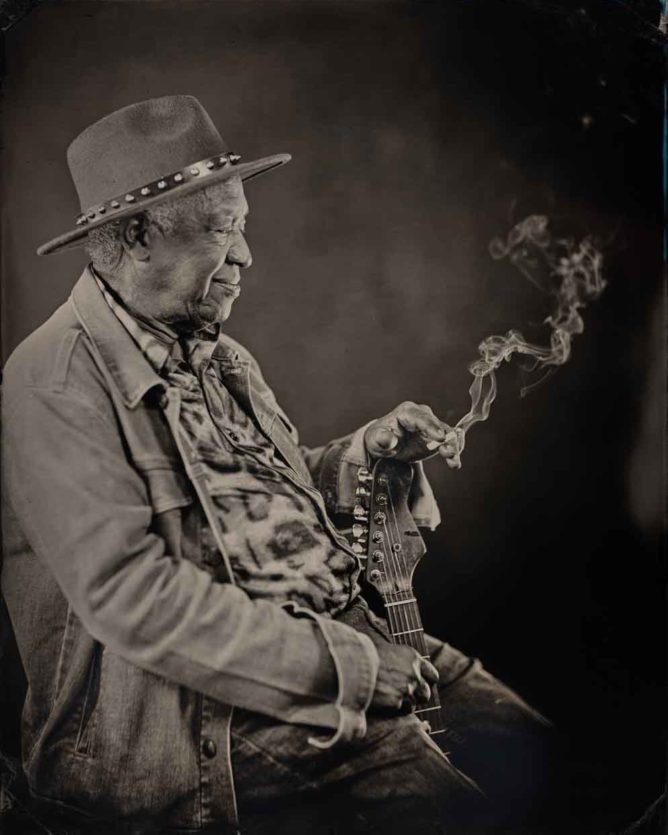

Like those boots, Hermon Hitson himself is unique in the truest sense of the word. No other human has the wild mix of experiences that make up Hermon’s life. And certainly no one plays the guitar like Hermon does — a mind-bending mix of psychedelic rock, the blues, rhythm & blues and soul music.

Sam Duffy, brother of Music Maker co-founder Tim Duffy, joined the Music Maker Blues Revue for their final set at Telluride. “It was Hermon’s turn,” Sam remembers, “and he said, ‘OK, we’re going to do Howling Wolf’s ‘Back Door Man.’ Then he just launched into this …”

Sam pauses for a long time, seemingly unable to muster the words needed to describe what he experienced playing with Hermon. “I’m still blown away,” he finally continues. “It was crazy. I’ve never … I can’t really describe it…. It was this psychedelic, LSD-feel blues. It, like, triggered me, back to ‘Wow, I think I’m tripping again.’ It was like, ‘What is going on?’”

“I’m walking off stage and I’m like, ‘Hermon, how did you … what were you doing on your guitar?’” Sam recalls. “I just accosted him as we were walking off stage. ‘How did you do that? What is going on here?’ He just smiled at me. He said, ‘I don’t know. I just played the guitar.’”

From Colorado to Memphis

He wore those same shoes to sessions in Memphis, TN.

“That was a good jam, man,” Hitson said. “The spirit was there with us.”

Recorded and co-produced by Bruce Watson at his Delta Sounds Studio in Memphis, Hitson’s backed on the new album by guitarist and co-producer Will Sexton and some of Memphis’ best musicians:

The cast includes Mark Edgar Stuart on bass, and Will McCarley on drums, plus Art Edmaiston on horns, Al Gamble on organ, and singer-guitarist Marcella Simien. Garage rock legend Jack Oblivian played guitar on “Bad Girl.”

“Tim Duffy at Music Maker asked me to produce Hermon with the Sacred Soul Sound Section backing him for a record that was intended to be released on another record label,” says Watson. He continues, “I was vaguely familiar with Hermon’s history but really had never heard him outside of some poorly produced CD releases from the ‘80s. Hermon arrived at the studio and from the first note of the soundcheck it was clear that this session was going to be special. We cut the record in two days. Hermon was unstoppable and the Sound Section was on fire.”

One Music

In the music business, there are certain sidemen — players who back the stars — who play with such prowess that they gain fame of their own. By all rights, Hermon Hitson should be one of those people. Over the years, he played with Jimi Hendrix, James Brown, Joe Tex, Bobby Womack, Wilson Pickett, Garnet Mimms, Major Lance, Jackie Wilson, the Drifters, the Shirelles, Hank Ballard & the Midnighters and many others. “I played behind Jackie Wilson and Sam Cooke on the same doggone show,” he said, recalling one night at the Royal Peacock. Along the way, he picked up every style of music that was popular in the early years of his career. Hermon’s cousin is Dave Prater (of Sam & Dave).

One night, Hitson was 100 miles south in Macon to see the flamboyant, influential guitarist and showman Johnny Jenkins. At the show he met a tall, slim musician who didn’t even own a case for his guitar.

“That’s the first time I saw Jimi,” Hitson said.

Arguably, the original seeds of psychedelic rock were planted after Hitson and Hendrix became running buddies in the early 1960s. Both were playing the Chitlin’ Circuit, tours that would load somewhere between ten and two dozen African American musicians on a bus and tour the South, playing Black nightclubs.

“The backwoods chitlin circuit! The greasy mouths and the greasy food, people have a good time, for real! The juke joints, man, where they dance all night and really appreciate your music! That’s where it was, buddy! People sharecroppin’, but Friday and Saturday come, boy, they’d shake a leg. All over Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama. But the money was tough. We’d have to hustle sometime in the pool halls, you know,” He told Wax Poetics Magazine.

Jimi and Hermon spent weeks together, Hermon says.

“Me and Jimi used to stay up all night, sitting on the bed, eating soda crackers and sardines, and drinking Coca-Cola and Pepsi,” Hermon recalls.

He moved from there to straight-up soul music, recording his own compositions — including the luscious “Been So Long” — in Atlanta, where he had settled, for labels like Royal, ATCO and Minit. He witnessed a girlfriend’s murder and was mistakenly arrested at first. He was innocent, but ATCO still dropped him from the label.

After the 1970s rolled in, Hermon wound up playing funk guitar, recording some tracks with the Ohio Players and releasing some of his own funk singles, including the powerful “Ain’t No Other Way,” a number firmly in the James Brown vein which he reprised on ‘Let The Gods Sing.’

“Hell, I never knew that man’s name was no Jimi-damn-Hendrix,” Hitson said with a laugh. “He was a great guy, man. He wasn’t no wild guy, talking wild. He was a mellow dude.”

Hendrix fit right in, staying at the Bellevue or Hitson’s apartment between tours.

“Sometimes he would stay over at my apartment with me and my wife,” at a two-story redbrick building that still stands at 738 Formwalt Street, Hitson recalled.

“He wouldn’t stay long,” he added.

“I was born in Philadelphia in ’43,” he says. “Then my father died, and my mother took me down where her people was, and that was in deep Georgia — a place called Ocilla, GA.” The tiny town, with population under 4,000, sits about 80 miles north of the Florida line in south central Georgia.

“I was only listening to country,” Hermon recalls. “And those guys really, really excited me. There was no Black radio for me to hear the Black guys doing music. So, country was all I knew besides gospel.”

Hermon told Wax Poetics, “Sharecropping, man, it was rough. I had to get up way early, cut wood for the stove, start the fire, feed the chickens and the hogs, milk the cows, eat, walk barefoot a mile from the farm to the street, then walk to school. And sometimes, boss man would try to run over us with their trucks… One time they drove into the ditch and ran over my cousin’s head, killed him. Nothing happened to them.”

To build a better life for her children, Hermon’s mother moved to Jacksonville, FL, where her brothers were, then soon moved Hermon and his brother there.

He started a local doo-wop group, the Stereophonics. One night the guitarist didn’t show, so Hitson grabbed the instrument and did his best on it, buying his own guitar the next day.

“That’s when everything busted out,” Hermon says. “I began to see these guys walking down the streets, man, with the head rags on their heads, with guitars tied around their neck, the harmonica blowing. I would see them sitting in front of me at the barbecue joints. They’re sitting and they’re drinking. These guys influenced me. It was the blues, man. I had the gospel and the country. Now, here I am, and all this mixture became one music to me.”

Back With Jimi in New York

Perhaps it was that fact — that all music became one music in Hermon’s mind — that kept him from making hits of his own in the 1960s and ’70s. No producer ever sat down with Hermon and told him to make the record he wanted to make, to take the pure creativity inside him and express it on vinyl however he chose.

Instead, producers wanted to insert the stylistically versatile Hitson into whatever kind of music they believed most likely to turn into a hit. “Once we got to Atlanta round ’62, it got better. This whole town was a whole lot different then. Auburn Avenue was like coming down Broadway: music jumping, lights beaming, man; people dressed real nice. Home of the Royal Peacock, Henry’s Grill, Treasure Island, Morocco Lounge—first club I played. I am in an entertainer’s town now, buddy!,” he said to Wax Poetics.

Hitson began working with Lee Moses, another soul singer and guitar player, introducing him to acid. Both of them worked with a producer named Johnny Brantley. In 1969, Hitson and Lee Moses opened for The Allman Brothers Band at Atlanta’s Piedmont Park. That night, Duane Allman joined him and Moses on stage at Mamie’s Diner, a Black-run club on Bankhead Highway that would welcome hippies, Hitson said. “We played all night long,” Hitson said. “Ain’t do damn separation there. Jimi come out there with me a couple of times.”

He told Wax Poetics, “See, I’d play the White rock clubs, then go play the Black afte-hours spots, and White people would follow. I was playing rock and soul. I was a real hippie, buddy! Had a cowboy hat or headband on,” continuing, “Hell, I even jammed with the Grateful Dead.”

Hermon’s first four recordings were issued on the Royal label. “Been So Long,” a slow soul ballad, was chosen as the single and was a regional hit after WLAC in Nashville, TN began playing it. Hermon released several other singles while in Atlanta.

Then, in the mid-1960s, he moved to New York City, where he once again hooked up with Hendrix. Early in 1966, Hermon began work on his own psychedelic rock album under the title “Free Spirit.” Hermon sang and played lead guitar, and Hendrix played bass on a few tracks that went unreleased by ATCO at the time. Those recordings wound up being the source of a controversy in the 1980s that brought Hermon’s name into the limelight in a different way. The title song of the album, “Free Spirit,” was released on two albums of music allegedly recorded by Hendrix and then “lost” to history.

That’s my song,” Hermon says today. “Jimi heard it, and he would go to the studio with me when I come to New York, because he was hanging out with [producer] Johnny Brantley, too. He [Hendrix] didn’t never play no lead on nothing of mine. And he didn’t sing on nothing of mine. In fact, back then he thought he couldn’t sing. We had to keep pushing him:

“Jimi would say, ‘I can’t sing.’ I’d say, ‘Man, you don’t have to be Wilson Pickett. All you got to do is sing like you sing.”

A few months later, the Jimi Hendrix Experience came together in the UK. The rest is history, a history that Hermon Hitson was not a part of.

In September, 1970, Hitson got a call saying Hendrix had died in London. “That was a hard pill to swallow,” Hitson said.

Hitson himself become hooked on heroin and estranged from his wife and children — just as James Brown warned him could happen to road musicians. After serving time for drugs and “running women,” Hitson worked as a snake-clearer in the sugar cane fields of south Florida, armed with a flamethrower.

He’d get clean and find purpose in the Nation of Islam, which led him to meet Muhammad Ali, and he even learned to paint from an influential Black artist in Atlanta.

Coming Back Into View

Hermon never stopped playing, but his career was mostly limited to nightclub gigs in his hometown of Atlanta. Hermon was realistic about where his career stood when he first met Music Maker’s Tim Duffy in 2021, unknown to all but the most hardcore record collectors, Hendrix fans, readers of Wax Poetics Magazine (who profiled him recently), and fans of the legendary Ponderosa Stomp festival (which had featured him both at its main festival in New Orleans and at a SXSW showcase in 2008). Though his early sides had recently seen a reissue anthology, “he realized he was invisible to everybody,” Tim says.

But Hermon soon agreed to join the Music Maker Blues Revue for its gigs at Telluride in September of that year.

Hermon proved himself on the Telluride stage for three days in a row, which lifted his spirits tremendously.

“That was great, man: the scenery and all the beautiful people, man,” he says. “The fans were so great, man. I can’t explain the whole deal of what I felt and what I saw. It was just so beautiful, man. And I would love to do that again.”

On the new album, Hitson also revives “Suspicious!,” another song attributed to Hendrix but with the vocals turned down in the mix to obscure Hitson’s singing and playing. Hendrix played bass on the sessions, which Hitson said were largely recorded in Atlanta.

“That was supposed to be my album,” Hitson said, reflecting on those sessions with Hendrix in the late 1960s. “All those guys were going to be sidemen.”

Hitson’s new album also features Hitson’s new performance of maybe his best-known R&B songs — the funky, frenetic “Ain’t No Other Way.” He also covers “Bad Girl,” written by his longtime bandmate Moses, and a 1972 single for Hitson.

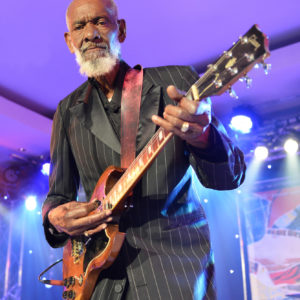

Doubtless, now that he is firmly set as a member of the Big Legal Mess and Music Maker families, Hermon will have that chance. And he’ll continue to flabbergast not only the audiences he plays for, but also the musicians he plays with.

Co-producer and guitarist Will Sexton attests to that, saying, “He comes down with wickedest grove filling the room, a perfect balance of soul and communication. He’s one of the old guard of the groove. He literally forced everybody to get loose and then tight. The most fun I’ve had in years. To play with a psychedelic pioneer with the guidance to take us in some trippy places.”

Get involved

& give back

The Music Maker Foundation is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that depends on thousands of supporters. Together, we work to meet the day-to-day needs of the artists who create traditional American music, ensure their voices are heard, and give all people access to our nation’s hidden musical treasures. Please contribute or shop our store today.